A pulley is a "wheel-and-axle" designed to support and change the direction of a rope, cable, chain or belt. The assembly of the wheel, axle and surrounding shell with anchor point, is often called a block, particularly when made from wood. A block can have more than one wheel sharing, but not attached to, a shared axle. To save space and keep lines as close to parallel as possible these are the most common type, but for our explanations imagine a sequence of single pulleys where alternate ones, starting with the first, are anchored to a ceiling (the maths is identical).

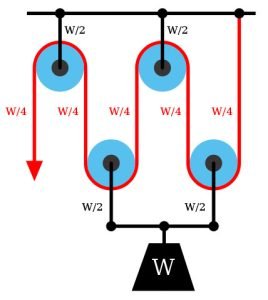

Assuming ideal parallel ropes mechanical advantage in pulley systems is derived from dividing the input force by routing the rope around additional movable pulleys. Fixed pulleys change direction but confer no mechanical advantage.

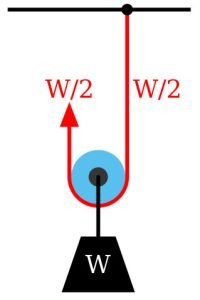

For example the edge case of a single fixed overhead pulley lifting weight W requires weight W to be balanced, analogous to a children's Seesaw. For a movable pulley where the rope is attached to the ceiling on one side, the movable pulley is dangling, attached to W and the tail of the rope is pulled upwards tension drops to W/2.

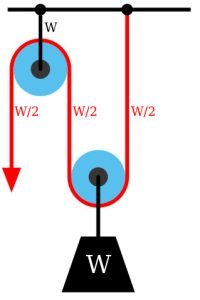

A simple two pulley system, anchored to the ceiling at the first pulley and the rope at the far end with the second pulley lifting W with its anchor point, needs an input force, or tension, of W/2 to balance.

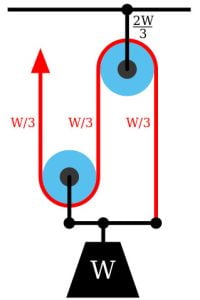

A three pulley system with W attached to pulley two and the end of the rope has tension of W/3. In practice these systems tend to use even numbers of pulleys so the load is always attached to a dangling block which has a hook, or eye on the casing rather than directly to the cable.

Cranes and marine rigging are two familiar contexts for the use of complex pulley systems. The cambelt or cam chain in a car engine may also be familiar but doesn't use mechanical advantage, it's just there to transfer force from the crankshaft.